This is part 2 of our three part series on Chinese futures markets. If you haven’t read them yet, here are part 1 and part 3.

Pssst…want to buy some Jujube?

The facts (not fantasies) about Chinese futures markets

In 1921, following the opening of the Shanghai Securities & Commodities Exchange, a series of exchanges were established in Shanghai and other cities, though most of them were forced to close in the subsequent years due to cash shortages. Only a small number of exchanges remained in Shanghai and Tianjin, but those were closed after the Chinese communist revolution and there would be no exchange trading in China until the economic reforms deepened under Deng Xiaoping in the early 1990s.

Soon, the number of futures exchanges rose, and a large variety of futures contracts were introduced to the market. Due to their relatively small lot sizes, these contracts were affordable even for non-professional investors and perceived as a quick way to make money. Regulation and oversight lagged behind, as there was no central authority to oversee and regulate these new markets. After the State Administration for Industry and Commerce enacted a new regulation in 1993, trading activity on some exchanges came to a stop. The liquidity started concentrating on a few exchanges and in few remaining products – a dynamic which sometimes caused extraordinary price events. During the 1995 Tianjin “327 Treasury bond futures incident,” a number of market players deliberately manipulated the market price with a large number of overdraft transactions.

In the 1996 Suzhou “red bean futures event,” market participants made use of the exchange’s faulty delivery terms and position limits, leading to extraordinary price volatility.

In 1998, the State Council reorganized futures markets to curb speculation and enhance hedging and price discovery functions. This was followed by a market contraction and flight of capital to other trading venues.

Nevertheless, already during that stage, Chinese futures markets were extremely active. In May 1995, for example, the “Zhengzhou Commodities Exchange turned over 320,000 futures contracts a day in mung beans alone,” tantamount to the same volume on the Chicago Board of Trade for 30-year Treasury bond futures on a sluggish day (see Derivatives Exchange; The Mung Bean and Its Adventures, The Economist, May 27, 1995).

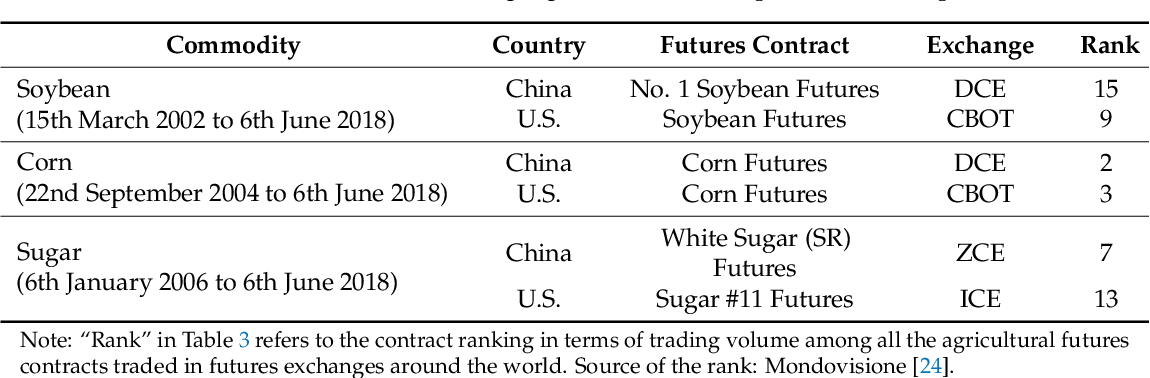

After two decades of development, there are now four futures exchanges: Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange (ZCE, established in 1993), the Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE, established in February, 1993), the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE, established in 1999), and the China Financial Futures Exchange (CFFEX, established in Shanghai in September, 2006). Among these, the DCE is the largest mainland futures exchange with the deepest liquidity according to the U.S. Futures Industry Association. China’s agricultural futures trading volume accounts for 58% of the global futures market – the highest of any country. And the SHFE is one of the key centers for metal trading globally. Several futures contracts are now among the most active contracts in the world, as already mentioned in part 1 of this blog post.

There are several commodities, e.g., metal and petroleum products, which are not exclusive to China. While the addition of these to an existing portfolio can be advantageous (increasing the overall portfolio liquidity), they are likely correlated to existing contracts on other exchanges. We witnessed this, for example, for gold and silver in part 1 of this series. Precious metals showed the highest correlation to existing contracts among the Chinese commodity futures.

However, some contracts are really unique. Among these are Bitumen (asphalt), pulp (a form of wood), PVC (plastic), fiberboard and blockboard (used for furniture), methanol (alcohol, chemical and not for consumption), green bean, sesame, glass, and polished round rice. That said, the contract that I found most interesting is Jujube, the Chinese date, which actually gave this post its particular name (if you didn’t already get the very very bad pun). It is one of the oldest cultivated fruits in the world, and it’s cultivation dates back to the Neolithic age some 7,000 years ago.

Jujube originated from the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River and covered a cultivation area of ~2 million hectares and an annual production of over 8 million tons in 2020. In comparison, coffee, a heavily traded commodity globally, reached an annual production of roughly 10 million tons in 2019, which shows that Jujube is not far off in terms of volume. Moreover, Jujube is distributed to at least 48 countries and to all continents except Antarctica. Commercial cultivation has been developed in many countries besides China, including Israel, the USA, Italy, and Australia. However, 98% of all Jujube plantations are located in China.

Amazing numbers. But there is more. “Jujube is becoming increasingly important in arid and semiarid marginal lands because of its endurance and adaptability to drought as well as barren and salty soil.” In addition the fruit is relatively easy to handle and “the costs of cultivation and management for jujube are significantly lower than those for other common fruit trees.”

Furthermore, Jujube is considered a “super fruit” to its many health benefits. “The contents of sugar, vitamin C, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (slows the ageing process and is a good candidate to mimic calorie restriction) are around 2, 100, and 1,000 times larger than for apples.” So it does not come as a surprise that the fruit is used extensively in Chinese medicine. Roughly 50% of Chinese herbal medicine prescriptions contain Jujube, which is significant given that traditional medicine has a similar status as conventional treatments in Chinese society. Last but not least, the fruit is easy to store and transport since most of it is used in dried form.

Given an environment of global warming, a trend toward a healthy lifestyle and dreams of eternal youth, this fruit clearly ticks many boxes. But as we know from our previous article on tea, not every commodity that is in high demand necessarily has a viable futures market. Jujube futures trade since April 2019 with expiries in January, March, May, July, September, and December. The contract is for physical settlement and the size is 5t/lot. From January to September 2019 the trading volume was 23.2mn contracts. Overall trading volumes in 2019 were twice the size of CME Live Cattle.

This figure has come down significantly to just 5mn contracts this year for the period from January to September. The price per ton is around 9-10k RMB, meaning 45-50k RMB per contract ($6.75k – $7.5k), which makes contracts quite affordable. (all numbers as reported by ZCE Monthly report 2020-10-23).

The average trading volume of roughly 28k contracts per day means that larger firms likely won’t trade this market. Assuming that we do not want to trade more than 2% of daily volume, it would allow us to trade $40mn of Jujube futures.

Not bad for a market you never heard about? Well, before you try to practice your Mandarin on your Chinese brokers, you should wait for part 3 of our series on Chinese futures markets, which deals with some peculiarities of these markets, such as trading conventions and market access.

So long and #happytrading